Over two million people call the Permian Basin home. Tens of millions more live on the Gulf Coast and along the pipeline routes that connect the Permian with its key markets. Communities living close to extraction sites are exposed to toxic air and water. Roaring flares light their night skies. Heavy truck traffic destroys their roads and poses heightened safety risks to their everyday lives. On the Gulf Coast, refineries, export terminals, and petrochemical plants are proliferating in marginalized communities that have long borne the toxic burden of our dependence on oil and gas.

These are just a few stories of impacted lives, and growing resistance.

Jim & Sue Franklin

When Jim and Sue met in Balmorhea, Texas a decade ago, they never imagined that the town, home to a beautiful state park and bustling with tourists, would ever become a hotbed of oil and gas production.

While many people came to Balmorhea for its beautiful natural springs, Sue Franklin came to Balmorhea for the rocks. Sue and a longtime friend, Leon, opened a store in downtown Balmorhea to sell rocks and minerals. At the store, Sue met Jim. Soon after, the Franklins were married and moved onto Jim’s land just outside of town. They didn’t know that the area would soon be catapulted into the center of the fracking boom.

Credit: Earthworks

As fracking became more prolific around Balmorhea, wells began popping up ever closer to their home. One well was just across the street. They could see more than 20 wells from their yard, most of which are owned by Primexx.

Then came the decline in their health. They began to experience consistent severe nosebleeds. Stabbing headaches often woke them in the night. Sue, who had never had respiratory problems before, was put on three different medications to breathe.

Gas flares threw off intense light and noise at all hours of the night, making sleep elusive. As torturous as that was, unlit flares took an even bigger toll on their health as they spewed methane and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air they breathed.

The Franklins submitted numerous complaints to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) with evidence of the invisible air pollution documented by Sharon Wilson using optical gas imaging (OGI). The TCEQ took action on one complaint and required the operator to make equipment repairs. Those repairs only lasted a few weeks before the site again released toxic compounds near their home.

After several years of continued exposure and deteriorating health, the Franklins relocated. When the agency that was supposed to protect them failed to do so, the Franklins hired a lawyer and eventually got a settlement allowing them to move. They left behind their property and the community that they had once hoped to spend the rest of their lives in.

Penny Aucoin & Dee George

Carlsbad, New Mexico is the center of New Mexico’s Permian oil boom. It’s economy rises and falls with the basin’s boom-bust cycles. The air often hangs thick with smog accumulated from the hundreds of wells that surround the town. Around Carlsbad, the required distance between oil and gas wells and people’s homes and schools is only 300 feet.

Dee George grew up just outside Carlsbad and has lived in his home for more than 40 years. Penny Aucoin, Dee’s wife, has lived there with him for more than a decade. A few years ago, WPX Energy drilled a well directly across the street from Penny and Dee’s home. That well was just one of many that have been drilled within their viewshed. There are so many, the ground often shakes.

Soon after the first well went in Penny and Dee’s family began to experience health impacts. Their son had such intense chronic nosebleeds, doctors chemically cauterized his nose. His nose began bleeding again within days of the procedure. Penny experiences blisters and splitting headaches.

Dee recounted a particularly bizarre interaction with a WPX representative. They were discussing the impacts of the nearest well on his family’s well-being when the representative asserted the house was too close to the well. As if the house had not been there 40 years before the well.

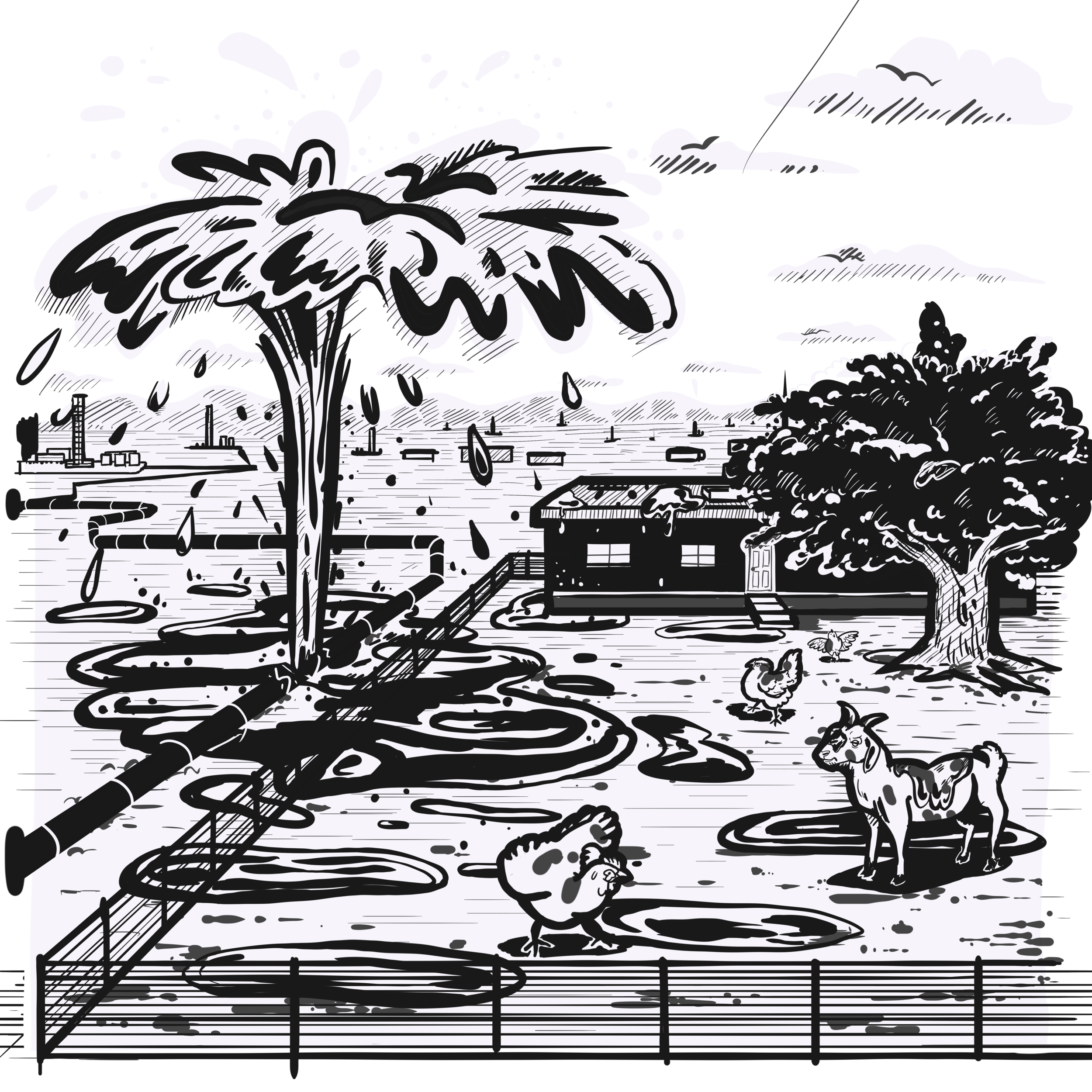

Penny and Dee’s nightmare is not limited to air pollution. In early 2020, a produced water pipe burst at the well. Produced water comes out of the well along with oil and gas. The water often contains heavy metals, bacteria, and frac fluids. It is also highly flammable and can even be radioactive.

When the produced water pipe burst, it showered their farm animals, land and home with the toxic water. Both Dee and their son had severe nose bleeds as soon as they went outside to investigate the commotion from the burst pipe. The whole family had to immediately barricade themselves indoors and turn off their air conditioning to breathe.

After the pipe was finally sealed, the operator made some limited efforts to resolve the problems it caused for the family such as cleaning the farm animals with a proprietary organic waste treatment solution. Penny worries about the non-organic components, like the heavy metals, as well as the produced water's radioactivity. The animals continued to suffer severe health effects ultimately causing the family to make the difficult decision to put them down.

The stench of the produced water seeped into the home and cannot be removed. The situation has devalued the property and rendered it impossible to sell. Eventually WPX settled with them. The contaminated lot and home are still owned by Dee’s family as they have been unable to sell it. It sits abandoned.

Credit: Jessica Lutz

Trap Spring and the Big Bend Region

The Big Bend region of Texas is home to sprawling ranches, magnificent canyons and a spectacular national park. Not the place you would expect to find a 42-inch fracked gas pipeline. Indeed, prior to the construction of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline (TPP), the Big Bend area was relatively untouched by oil and gas. The 148-mile pipeline would bring gas from the Permian Basin to the Mexican border for delivery into the Mexican gas network.

The first thing some locals knew about the project was when pipeline surveyors from Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) came on their property uninvited. That didn’t sit well with them.

Many landowners were concerned about the pipeline abusing eminent domain to build the project on their land, whether they wanted it or not. All a company has to prove to use eminent domain is that a pipeline has signed some contracts with customers. Many ranchers resented their land being seized. They also feared a pipeline failure and explosion, which could cause a major brushfire. The area is dry and lacks robust fire fighting capability as the region relies on volunteers and aid from ranchers for firefighting.

Many in the community worried about a leak tainting drinking water and erosion and destruction of natural habitats during construction. They also feared that the development of such a large pipeline would galvanize the development of oil and gas wells in the area to feed the pipeline.

In 2015, community resistance coalesced into the Big Bend Conservation Alliance. However, opportunities for the public to comment on the project were rare. Although the pipeline crossed the border with Mexico, the project was designated as an intrastate pipeline by the Texas Railroad Commission. This lowered the criteria for permitting. There was no mandate for an environmental impact study.

A push by the Alliance to get the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to take over permitting and conduct an environmental impact study failed. With decreasing odds of stopping the project, the Alliance turned its sights onto rerouting the pipeline to avoid a small part of Brewster County known as Trap Spring.

Trap Spring is an archaeological treasure where numerous indigenous artifacts have been found. ETP sent an archaeologist to the site and they recommended rerouting the pipeline in order to avoid destruction. But it didn’t happen. Artifacts were destroyed despite an offer from a neighboring rancher to allow them to reroute the pipeline through their land.

The Trans-Pecos Pipeline began operation in 2017. For several years, it went underutilized prompting the Big Bend community to question why the process to approve and install the pipeline was so rushed. The pipeline spilled hydrostatic testing fluid on the banks of the Rio Grande when it was first started. During remediation for the spill the operators planted invasive Salt Cedar to replace the native vegetation that they destroyed. Just one of the myriad adverse impacts caused by the Permian Climate Bomb.

At every stage of the oil and gas production process, operators come into conflict with frontline communities. Often these marginalized communities attempt to resist. But government at every level is captured by the industry.

Take Action

You Can Help Defuse the Permian Climate Bomb.

Sign up to learn more about the role you can play in ending this crisis & get updates when future parts of this series are released.